Butterfly disease: A disorder that makes skin as delicate as butterfly wings

"Butterfly disease" is a potentially fatal, inherited disorder that causes patients to blister very easily.

Disease name: Epidermolysis bullosa (EB), or "butterfly disease"

Affected populations: Butterfly disease is estimated to affect around 1 in 50,000 children, if you count all subtypes of the disease together. EB is equally common among males and females, as well as across races and ethnicities.

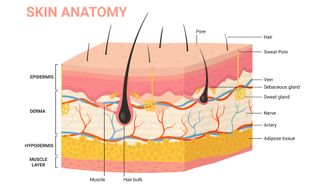

Causes: Butterfly disease refers to a group of rare, inherited diseases that cause the skin to be very fragile and to blister easily. There are around 30 subtypes of butterfly disease, and these are sorted into four main groups that differ based on the part of the skin that is affected.

The most common form of the disease, which affects 70% of EB patients, is known as epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS). Patients with EBS carry genetic mutations that affect the outermost layer of their skin, called the epidermis. EBS is usually an autosomal dominant disorder, meaning that children who inherit just one copy of the mutant gene from a parent will develop it. Rarely, the disease passes in an autosomal recessive pattern, in which a child needs two copies of the gene — one from each parent — to develop it.

Related: 'Butterfly disease' makes the skin incredibly fragile, but a new gene therapy helps it heal

Symptoms: Patients usually begin to develop symptoms of butterfly disease at birth or during early childhood. Symptoms can vary from mild to severe, and they differ across the subtypes of the disease. Common, universal symptoms of EB include having skin that blisters easily, especially on the hands and soles of the feet. These areas of the body also often have thickened, scarred skin. Mild forms of butterfly disease can improve with age and aren't fatal, but patients with severe forms typically don't live beyond age 30. That's because severe cases can lead to life-threatening infections and damage internal organs.

Treatments: There is currently no cure for butterfly disease. However, appropriate wound care — for instance, draining blisters and using nonadhesive bandages and dressings to cover wounds — can help patients manage their symptoms. Drugs can also be taken to relieve the itching and pain associated with the blisters, and antibiotics can treat any related bacterial infections. Some patients may also require surgery if the disease causes their esophagus to constrict or if they have problems using their hands due to excessive scarring.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new gene therapy gel for the treatment of a specific type of butterfly disease in patients who are at least 6 months old. Called dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, this form of the disease is caused by mutations in a gene that codes for a type of collagen in the skin. The gene therapy, known as Vyjuvek, delivers working copies of the collagen gene into patients' cells.

This same gene therapy was also adapted into eye drops in 2023. It was used to help restore the vision of a teenage boy who was legally blind due to scarring of the eyes caused by butterfly disease.

The FDA has also approved another gel, called Filsuvez, for the treatment of wounds in patients 6 months and older. The gel, made from birch bark, is approved for only certain types of butterfly disease.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily is a health news writer based in London, United Kingdom. She holds a bachelor's degree in biology from Durham University and a master's degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has worked in science communication, medical writing and as a local news reporter while undertaking journalism training. In 2018, she was named one of MHP Communications' 30 journalists to watch under 30. (emily.cooke@futurenet.com)

Most Popular